I’ll have the soup du jour and the braised beef short rib. Thank you.

In a matter of days, those words will flow from our mouths as we sit contentedly under the glass canopy protecting Café Sebastienne from a chilly Kansas City January. The much anticipated annual Restaurant Week provides the opportunity, both to indulge in some of our area’s tastiest cuisine, as well as learn about the establishments offering it. We thought we’d join in, and share some history about Café Sebastienne, which happens to include a brief chapter concerning IAA.

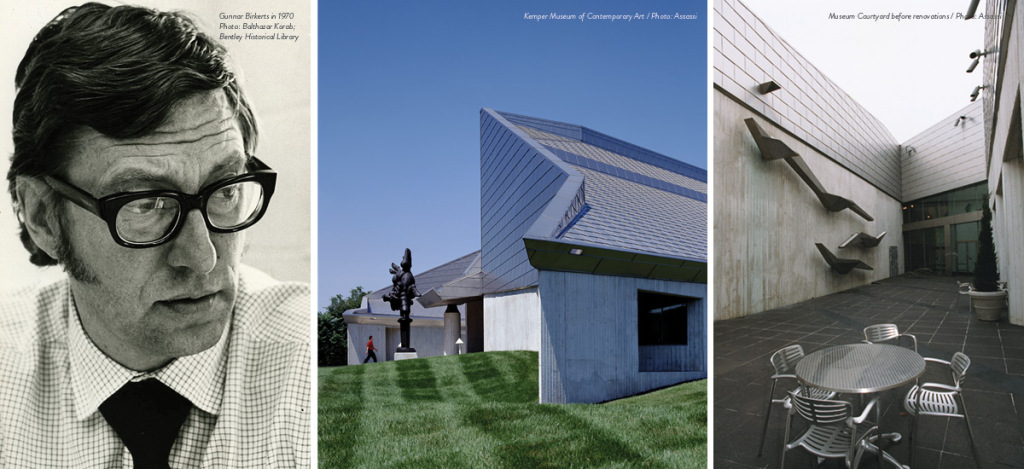

The Kemper Museum, constructed in 1994 and housing the café, was designed by one of the most distinguished late-modernist architects, Gunnar Birkerts. Born in 1925 in the Latvian capital, Riga, a young Birkerts earned the degree of Diplomingeneur Architekt from the Technical University of Stuttgart, Germany before moving to the United States in 1944. Once here, he practiced at Perkins + Will, and then under Eero Saarinen before going out on his own in 1959. Since then, Birkerts has completed dozens of iconic buildings inspired by unique circumstances. Over the course of his career, the Latvian architect earned a reputation of deciding on a design at the last minute. Despite how it might sound, that was a good thing. It allowed Birkerts’ work to be guided by an individual project site and situation, free of preconceptions (1). He described his creative process, entirely dependent on a commitment to authenticity and originality, like this:

I do synthesize everything in my mind. I don’t have any attachment or particular interest with any direction of philosophy or dogma – I have design principles. I don’t believe in any architect’s form-giving whatsoever. If I design a building, I might look at a published building – not to be influenced, not to do what’s been done before, (but) just to stay away from influence. The mind is not that clear that it would not reproduce something it saw from years back (2).

Much of Birkerts’ architecture is about intuition (3). His forms support his material choices, and although those materials – concrete, stone, metal, glass – are rigid in nature, there is fluidity in much of his work. This may be attributed to Birkerts’ choice to embrace rather than challenge their inherent characteristics. The Kemper Museum, primarily concrete and steel, is described by Birkerts as a free-flowing space, unfolding as it progresses. Continuing, he says:

It is not compartmented, but allows flexible transitions from one space to the next…a continuous ribbon of daylight provides continuity and direction within the museum and a connection to the outside. The weaving of nature into the building form further establishes a visual dialogue within the context and a space for outdoor exhibitions (4).

The museum’s connectivity and rejection of boundaries is sensed from first glimpse of Tom Otterness’ Crying Giant where the collection is virtually spilling out onto the front lawn, to the cascading front stairs, into the light-infused main atrium, through the exhibition spaces, and into Café Sebastienne at the core of the building. The transition from one space to another, and outdoors to in, is easy and natural. The skillful and unforced material interaction is crucial in achieving this balanced effect and flexibility of space despite such crude elements. It also happens to be a hallmark of Birkerts’ varied designs.

The building sits in stark contrast to neighboring Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, known for its neoclassical architecture and idyllic sculpture park. Instead, the Kemper is articulated by board-formed concrete walls and a stainless steel roof. According to Birkerts, “The dynamic building form…presents the distinct personality of the museum while using an informal vocabulary that is not related to any architectural historical style, yet is expressive and accommodating” (5). The simple, yet evocative materials and their relationship with one another position the museum firmly within a modernist language, but quite artfully, as Birkerts shared, without asserting allegiance to any movement or style in particular. If one might argue Birkerts possesses a style at all, it would be this: continuously producing original designs in composition, engineering, and materiality, unique unto themselves (6). The Kemper is Kansas City’s proof.

So, when the museum commissioned IAA to renovate the existing dining space and outdoor courtyard into a gourmet café, our team set out to deliver a very thoughtful and expressive design sensitive to the building’s original vision. The transformation was special. Simple, but sophisticated materials and execution had a major functional impact without drastically altering the visual experience.

So, when the museum commissioned IAA to renovate the existing dining space and outdoor courtyard into a gourmet café, our team set out to deliver a very thoughtful and expressive design sensitive to the building’s original vision. The transformation was special. Simple, but sophisticated materials and execution had a major functional impact without drastically altering the visual experience.

True to Birkerts’ original design, IAA incorporated meticulously matched, board-formed concrete and flat-seam stainless steel shingles into the addition, seamlessly integrating it into the existing structural fabric. Above, the space is enclosed with a glass roof supported by a delicate steel structure. Recessed within the existing walls, the sloped skylight is only visible from inside the café, preventing any aesthetic alteration from outside the museum. Due to the height of the space and its infusion with natural light, the café still reads very much like an outdoor courtyard, obscuring the distinction between the indoors and nature.

About his design, Birkerts wrote, “The dynamic building is expressive of the constant progression of modern art ” (7). Like the art housed within, the museum itself blurs lines, causes people to stop and think, and responds to and progresses with the environment in which it is situated. Since its completion, functional demands of the museum have evolved. Today, gourmet cuisine is one of those. So, with restaurant week upon us, we urge you to visit this local landmark where you’ll find much more than a (delicious) warm meal. And don’t worry, you can’t go wrong – braised beef short rib or creamy polenta – it’s a win-win.

———-

1 Sisson, Patrick. “Where History Meets the Future: The Unfinished Master Plan of Tougaloo College.” Curbed, 2016. Web. 15 July 2015 < http://curbed.com/archives/2015/07/15/tougaloo-gunnar-birkerts-campus-masterplan.php>